In the first module, I will be talking about the health and economic burden of consumption of tobacco, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages or SSBs and how health taxation is good for health and the economy.

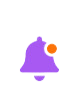

Let’s first set the scene, global estimates indicate that tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy diets are responsible for about 17 million premature deaths and for generating significant economic costs annually. Tobacco kills 8 million people every year and costs the global economy 1.8% of gross domestic product or (GDP). Alcohol use kills 2.6 million people every year and costs the global economy 2.5% of GDP. Unhealthy diets, and more specifically obesity and diabetes, kill 6 million people every year and cost the economy 5.2% of GDP.

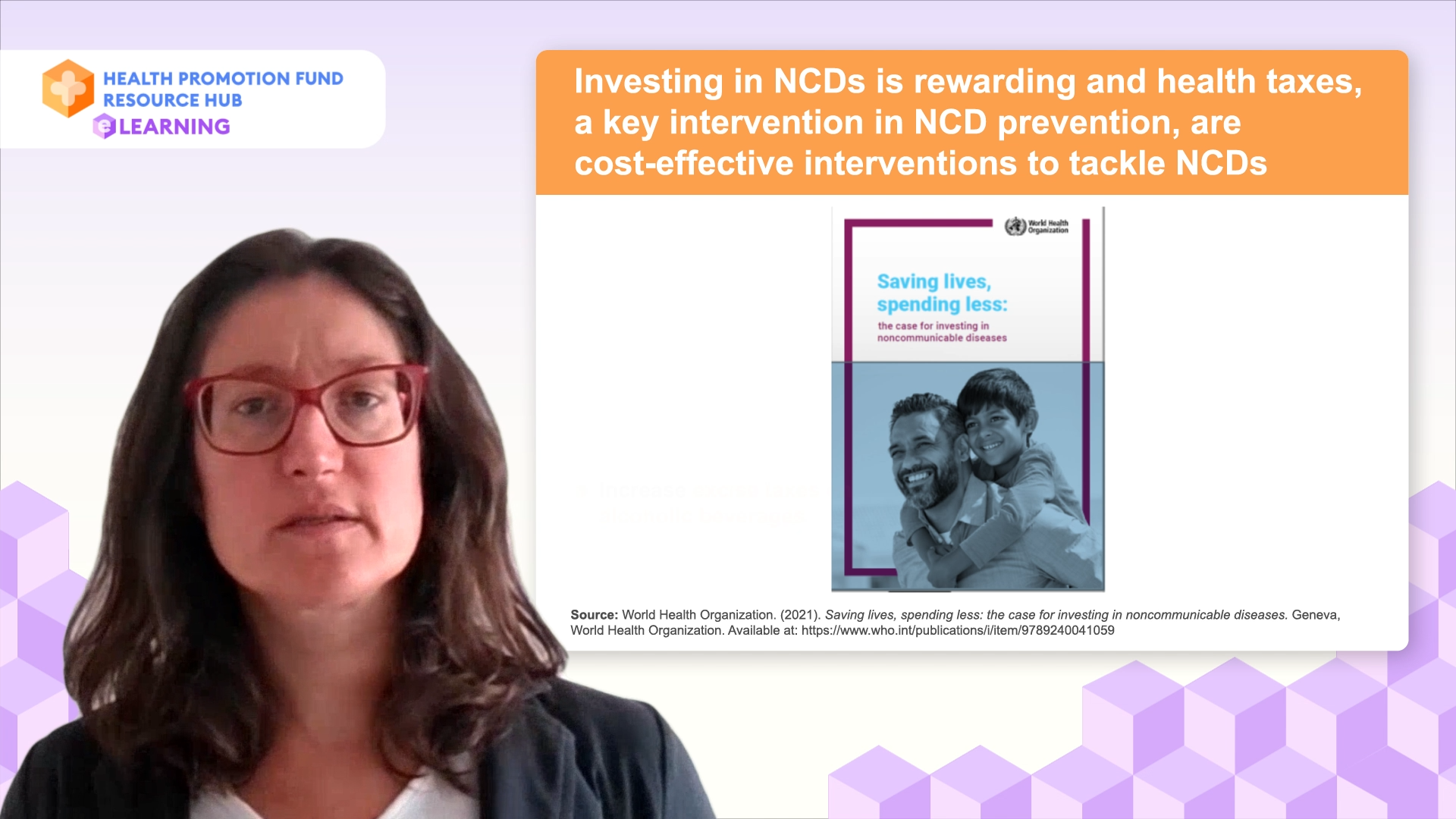

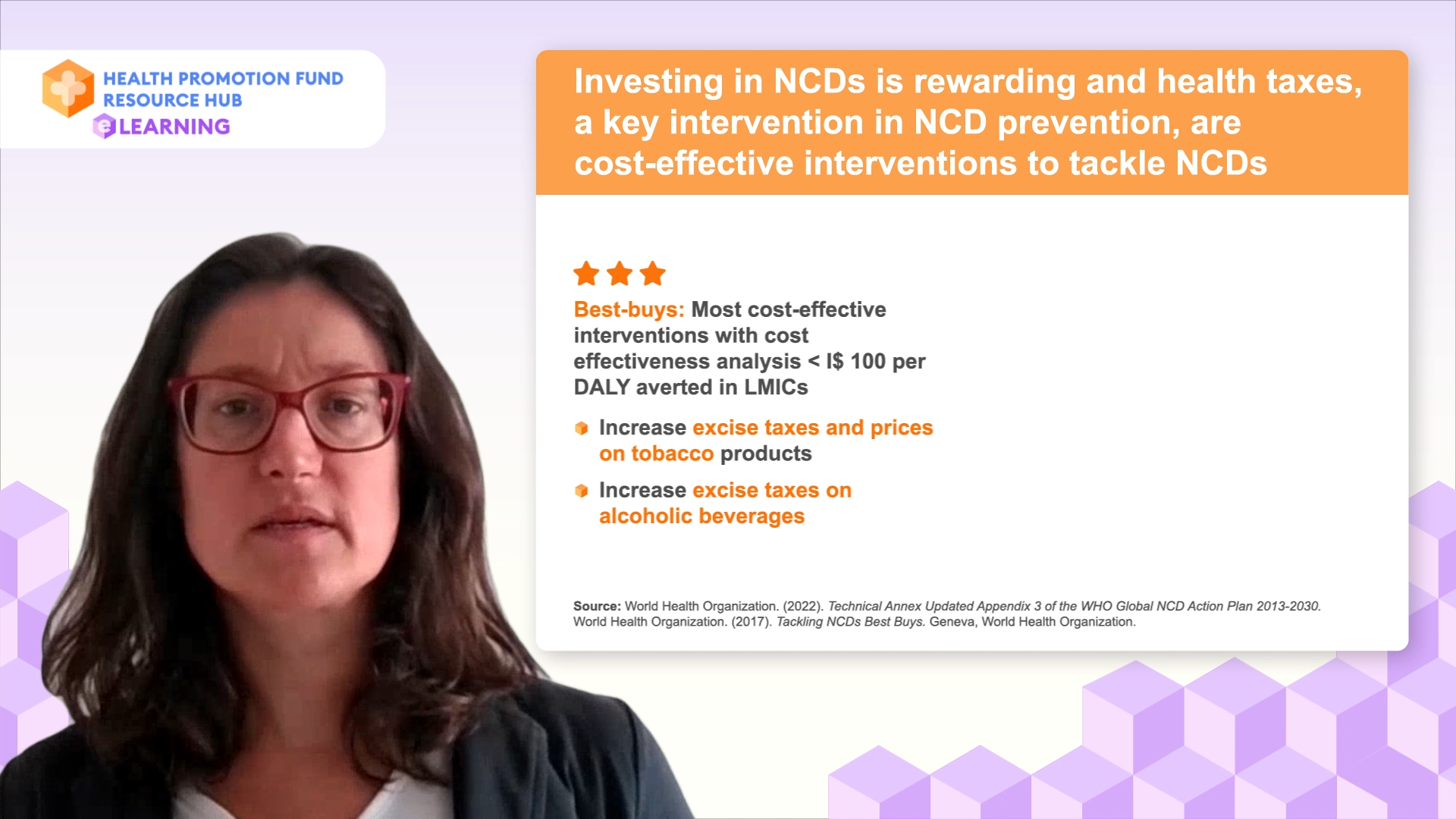

But the good news is that investing in the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is rewarding and health taxes, a key intervention in NCD prevention, are cost-effective interventions to tackle NCDs.

Global estimates have shown that investing USD 1 in tobacco control of which taxes are a key component will yield a return of USD 7.11 in reduced costs from deaths and diseases averted and averted loss in productivity. On the other hand, investing USD 1 in alcohol control of which taxes are also a key component will yield a return of USD 8.32 in reduced costs from deaths and diseases averted and averted loss in productivity.

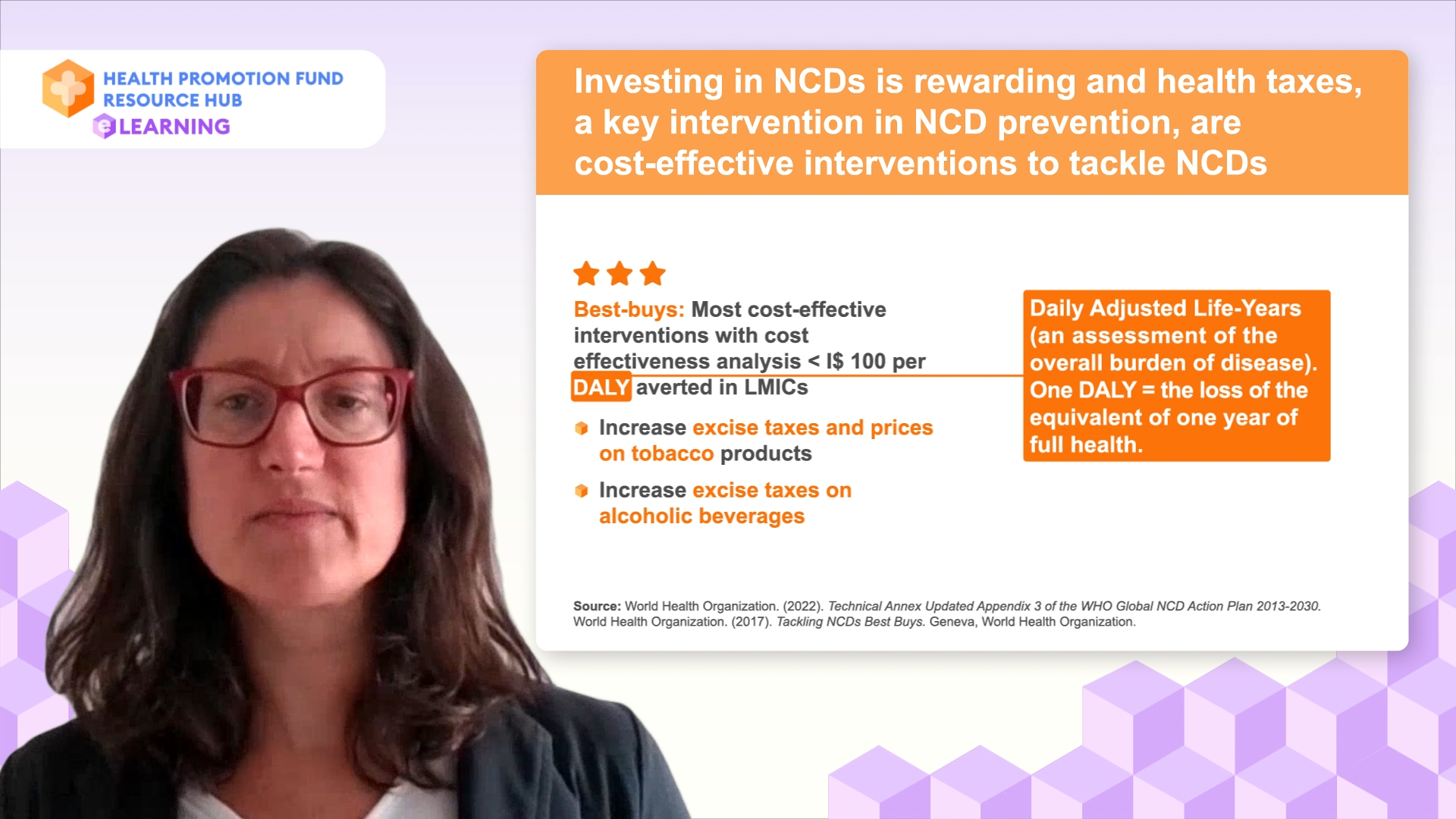

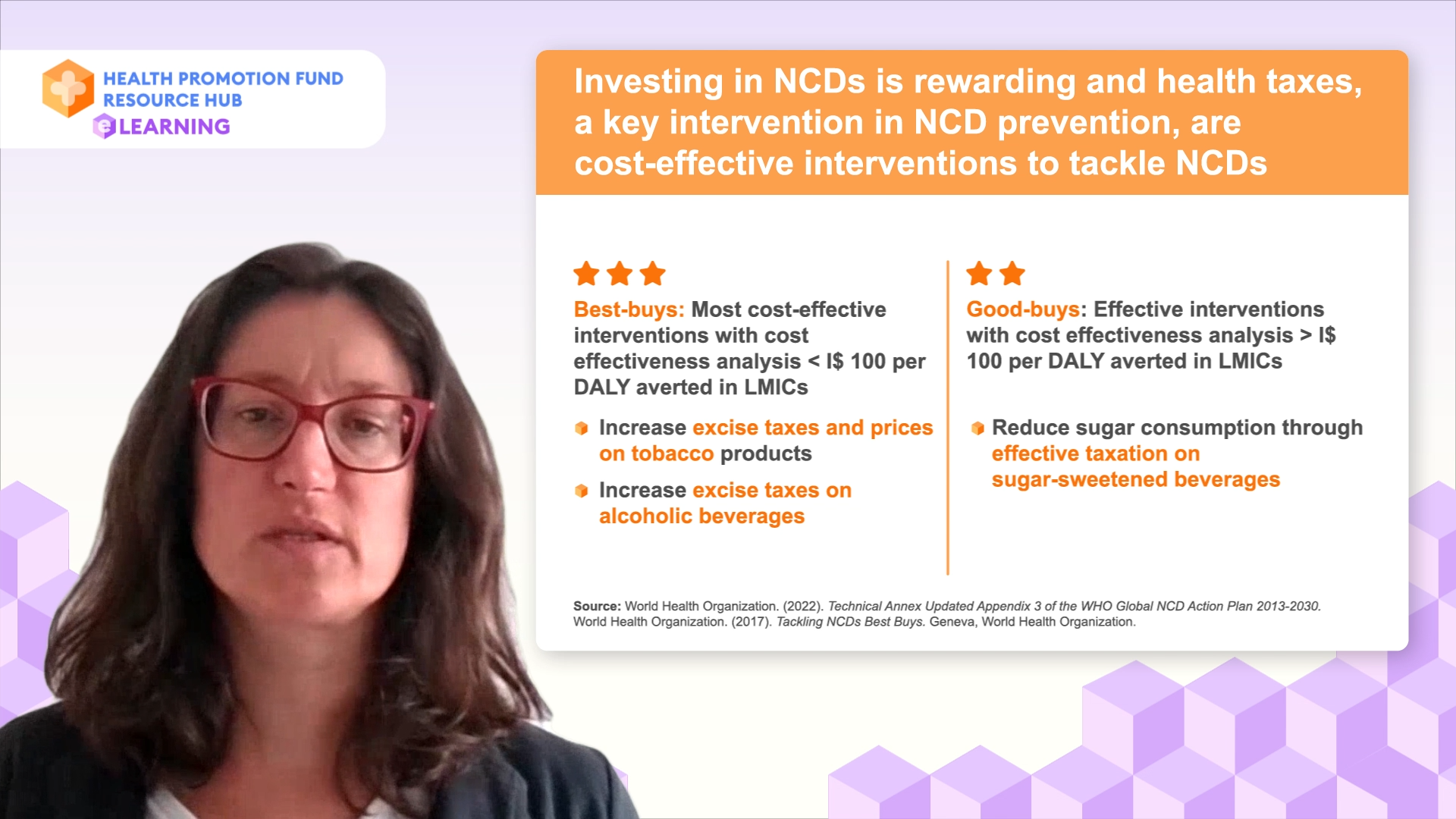

Health taxes are considered very cost-effective with tobacco and alcohol taxes being “best buys” which means they cost less than 100 international dollars ($) per DALY averted in low-and middle-income countries.

So what do we mean by DALY? A DALY is daily adjusted life-years. It is an assessment of the overall burden of disease. One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.

Finally, for the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages, evidence shows that they are good buys which means they cost a little more than 100 international dollar ($) per DALY averted in low-and middle-income countries and they are cost-effective and worth implementing by government to reduce the consumption of sugary drinks.

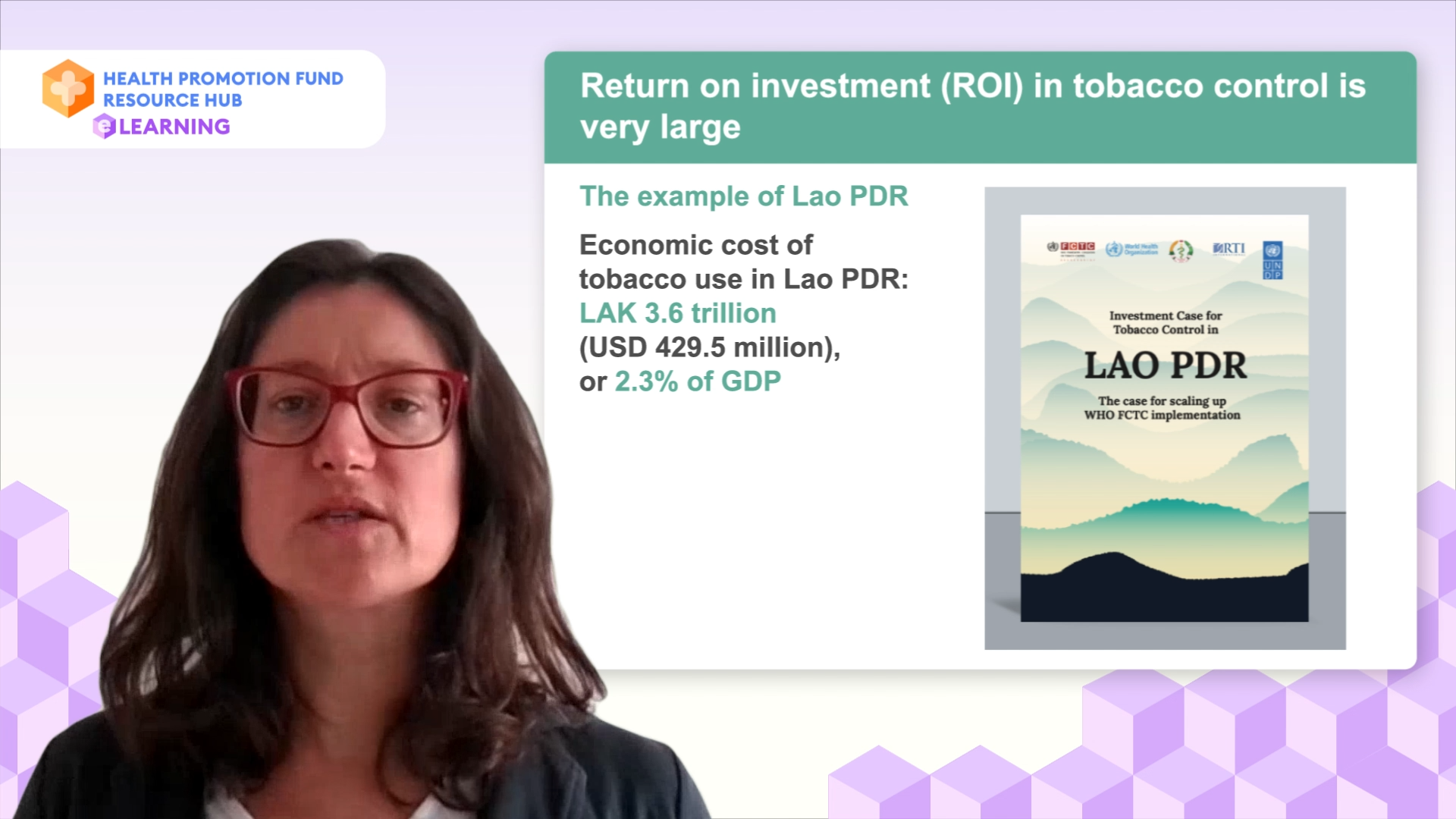

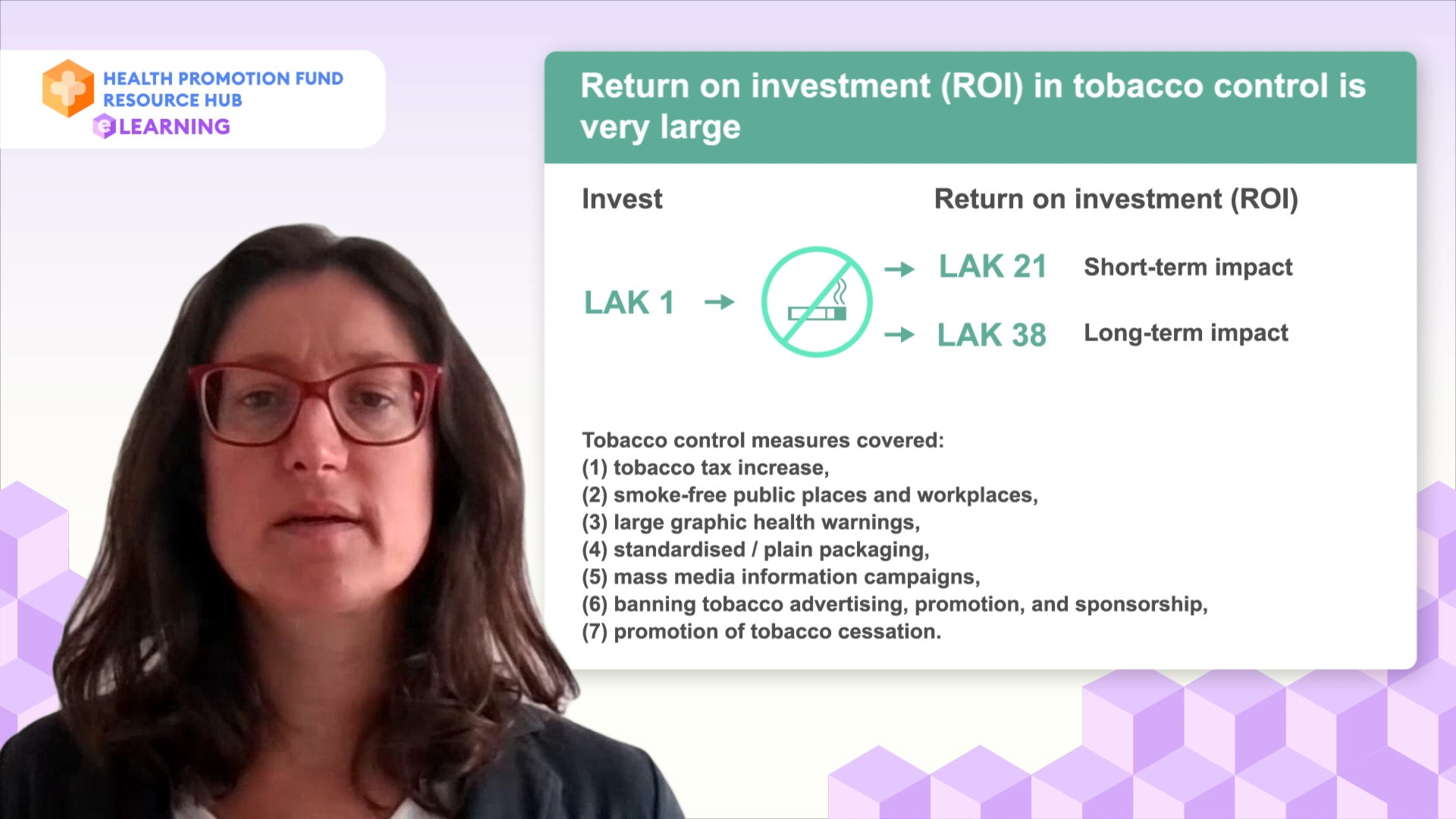

Estimates of economic gains from tobacco control, including tobacco taxation at country level are numerous and show the substantial benefits countries can accomplish if they effectively reduce tobacco use through strong prevention measures. Here is an example of a study undertaken in Lao PDR, which shows that tobacco use currently costs 2.3% of the GDP. Investing in strong tobacco control measures, including tobacco taxation pays back.

For every 1 Lao Kip (LAK) invested in tobacco control will bring in as much as 21 LAK in the short-term, the benefits are higher in the long-term with 38 LAK, that is because many of the health benefits can be seen in the long-term.

Looking at investments beyond just tobacco control, savings from investments in NCD prevention and control policies are also clearly substantial. A study in Jamaica looking at the impact of implementing tobacco and alcohol policies (including taxation) and scaling up clinical interventions to treat cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, depression, and anxiety would bring in large returns.

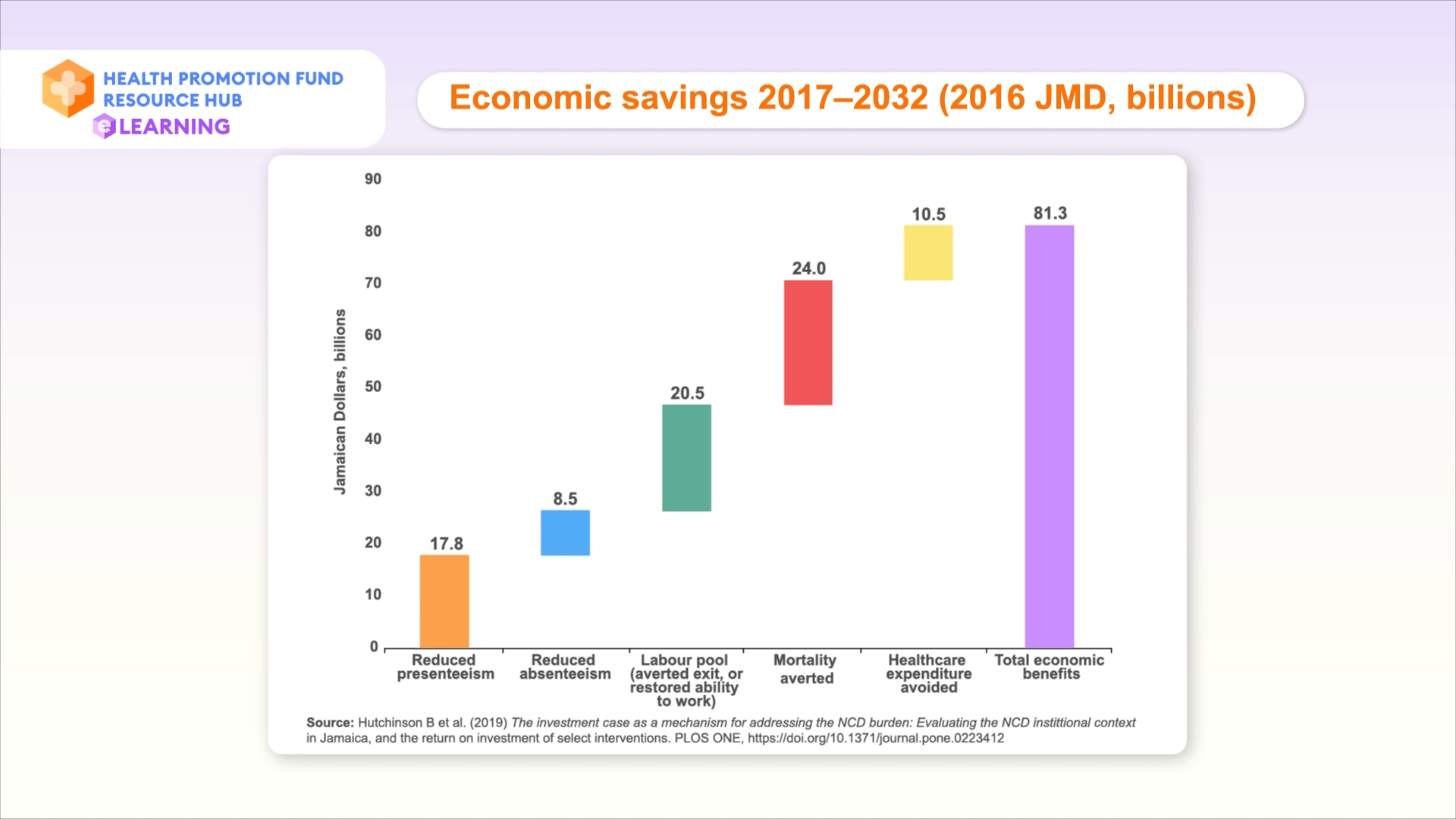

In the graph, the economic savings (in monetary terms) are broken down into different components which include reduced presenteeism (that is working at reduced capacity), reduced absenteeism (which is absence from work), averted loss of labour or restored ability to work along with mortality averted and healthcare expenditure avoided.

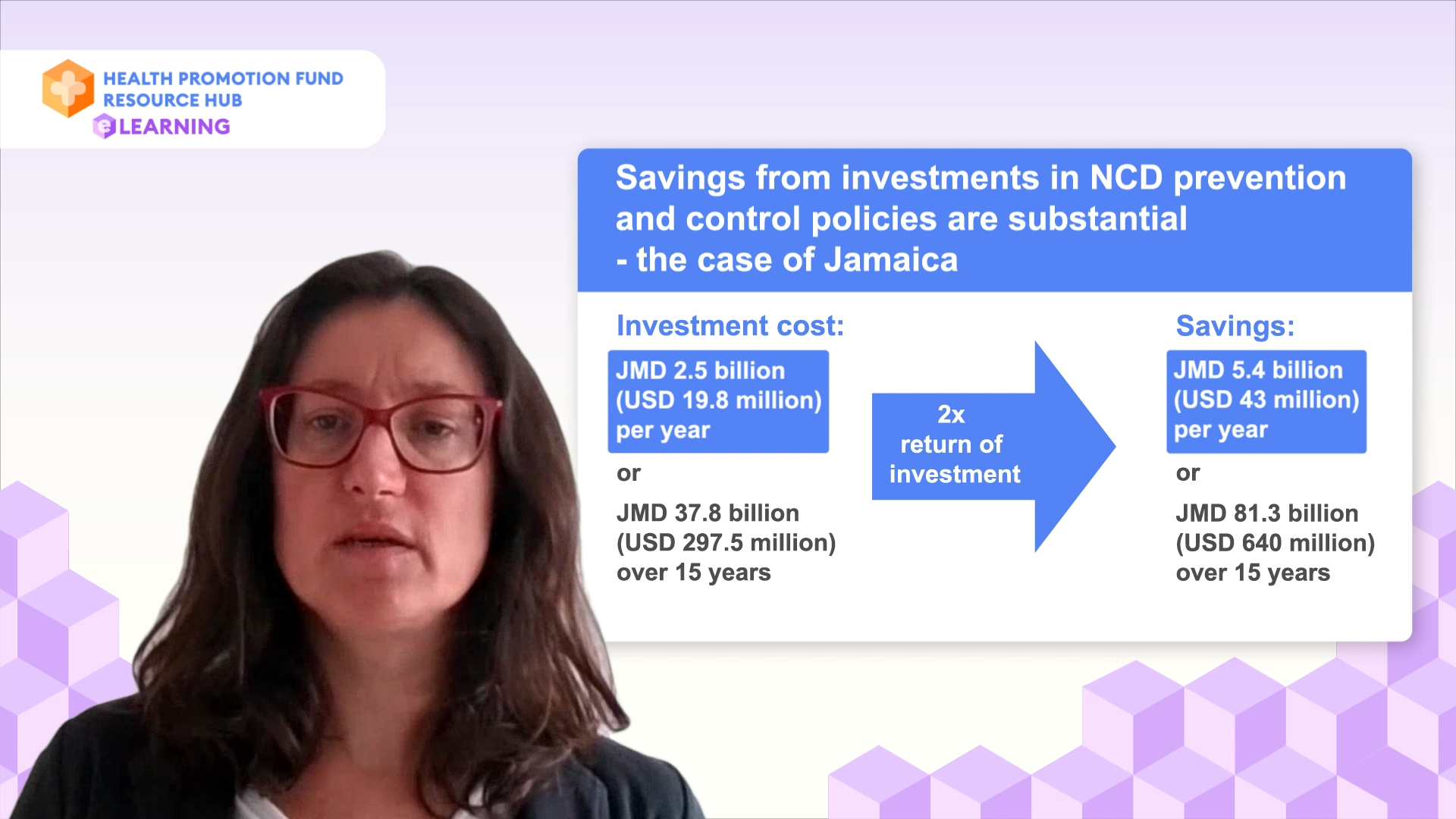

Investing the equivalent of JMD 2.5 billion or USD 19.8 million per year, would bring in economic returns twice as much as what was invested, or JMD 5.4 billion (USD 43 million) per year.

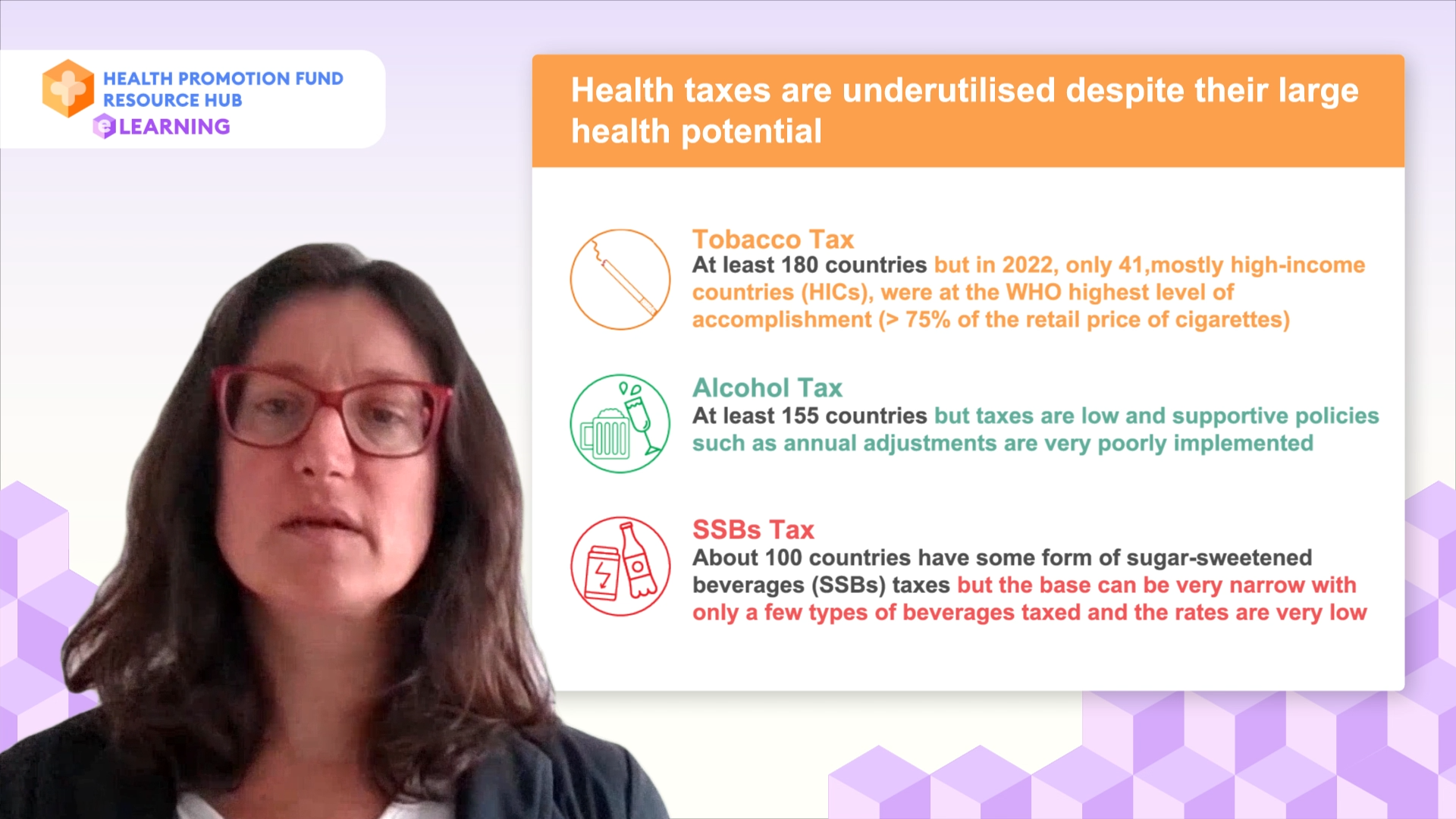

Despite the evidence of cost-effectiveness of health taxes and the clear economic benefits of the prevention of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages, those taxes are unfortunately underutilised. Most countries tax tobacco products but in 2022, only 41 countries implemented taxes at a high level of achievement, that is having taxes representing 75% of the retail price of cigarettes or more. For alcohol, at least 155 countries tax those products but taxes are low and supportive policies such as annual adjustments for the tax to increase are very poorly implemented. For sugar-sweetened beverages, about 100 countries have some form of SSB taxes but the base can be very narrow with only a few types of beverages taxed and the rates are very low.

For the next section, we will learn about “How much tax increase is needed for health and fiscal gains?”. I will see you in the next section.