2.2 How much tax increase is needed for health and fiscal gains?

Welcome. The speaker for this module is Ms Anne-Marie Perucic, Economist, World Health Organization (WHO).

Choose between video, audio or transcript to learn about this section.

Audio:

Hi again, my name is Anne-Marie Perucic, I am from the World Health Organization (WHO). Previously, we have learned about the health and economic burden of consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages and how health taxation is good for health and the economy.

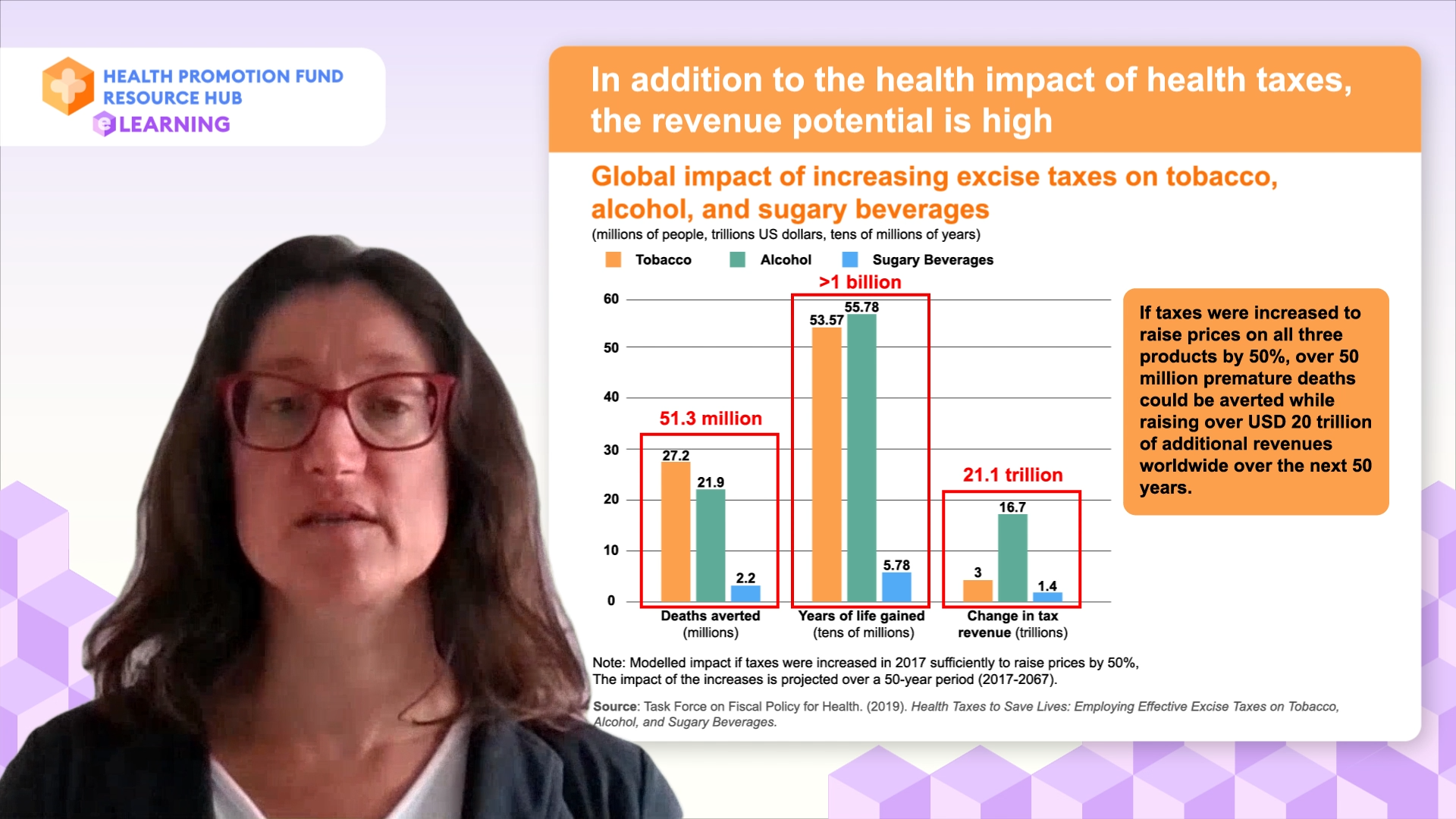

In this module, we will look at “How much tax increase is needed for health and fiscal gains?”. In addition to the health impact of health taxes, the revenue potential is high.

A study from the high-level task force on fiscal policy for health published in 2019 looked at the global impact of a one-time increase of tax on alcohol, tobacco, and sugary drinks leading to a 50% increase in prices. This increase would avert over 51 million deaths and improve health overall with more than a billion years of life gained over the next 50 years. At the same time, the tax increase would generate an additional USD 3 trillion from tobacco products, USD 16.7 trillion from alcohol, and USD 1.4 trillion from sugary drinks, this is over USD 20 trillion over the next 50 years.

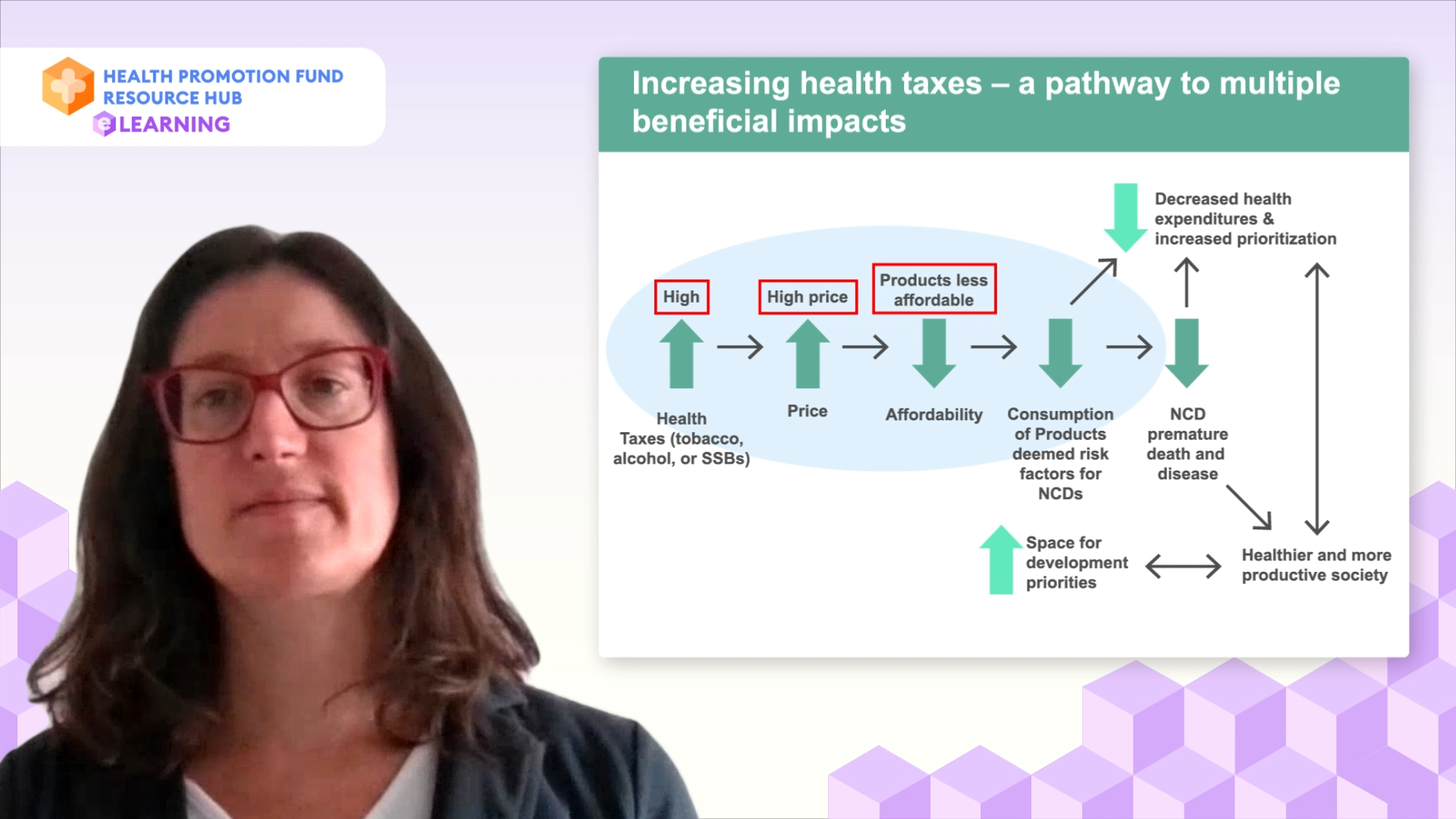

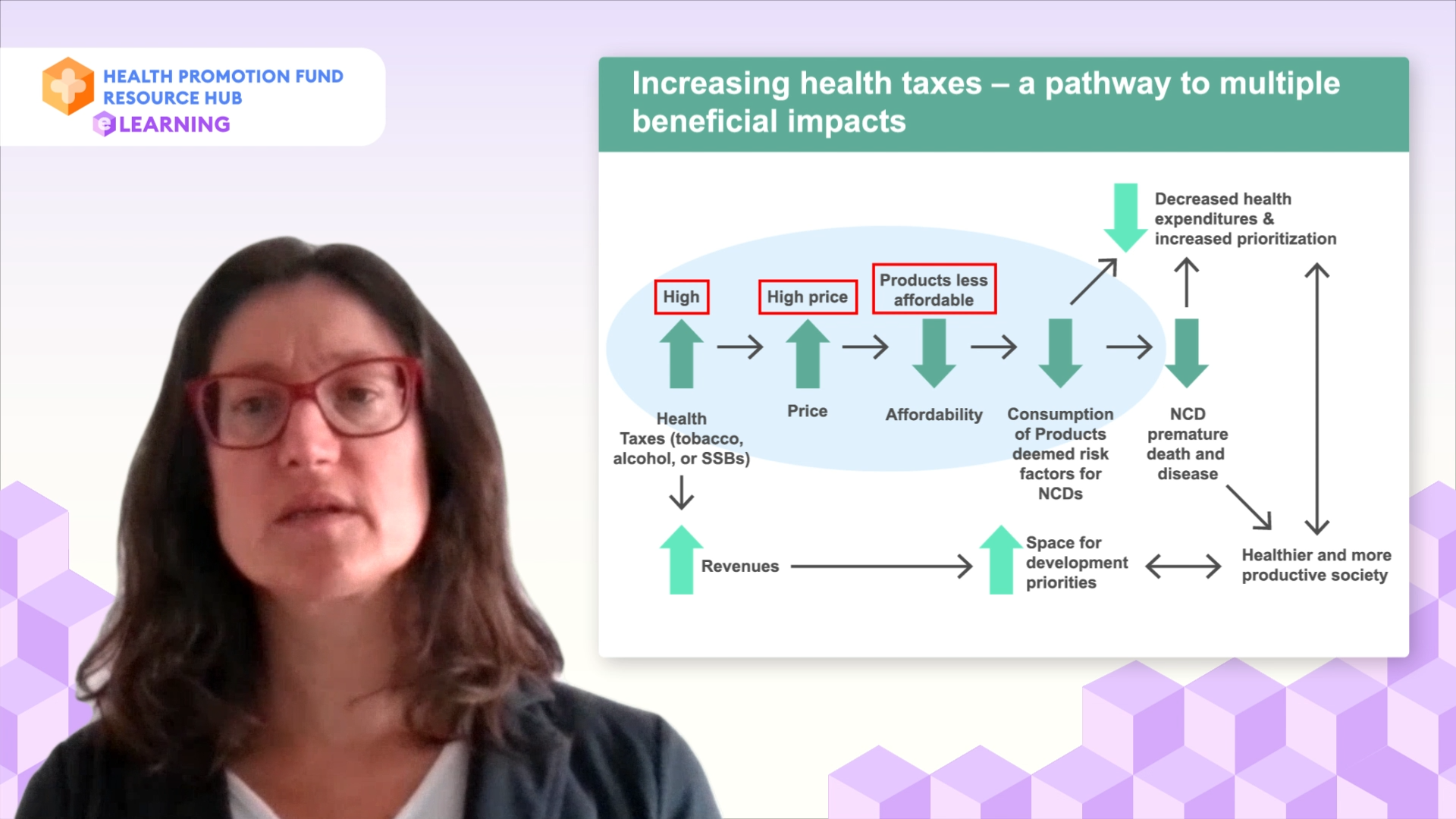

So what is the pathway from a tax increase to the revenue and health impacts we have been talking about? An increase in the tax on tobacco, alcohol, or SSBs that is high enough will increase prices, higher prices that make products less affordable reduce consumption of the harmful products, this reduces premature deaths and diseases from NCDs leading decreased health expenditures and a healthier and more productive society with reduced economic costs leading to more space for development priorities.

In parallel, the tax increase will lead to revenue increases which also provides more space for development priorities benefiting countries’ populations overall.

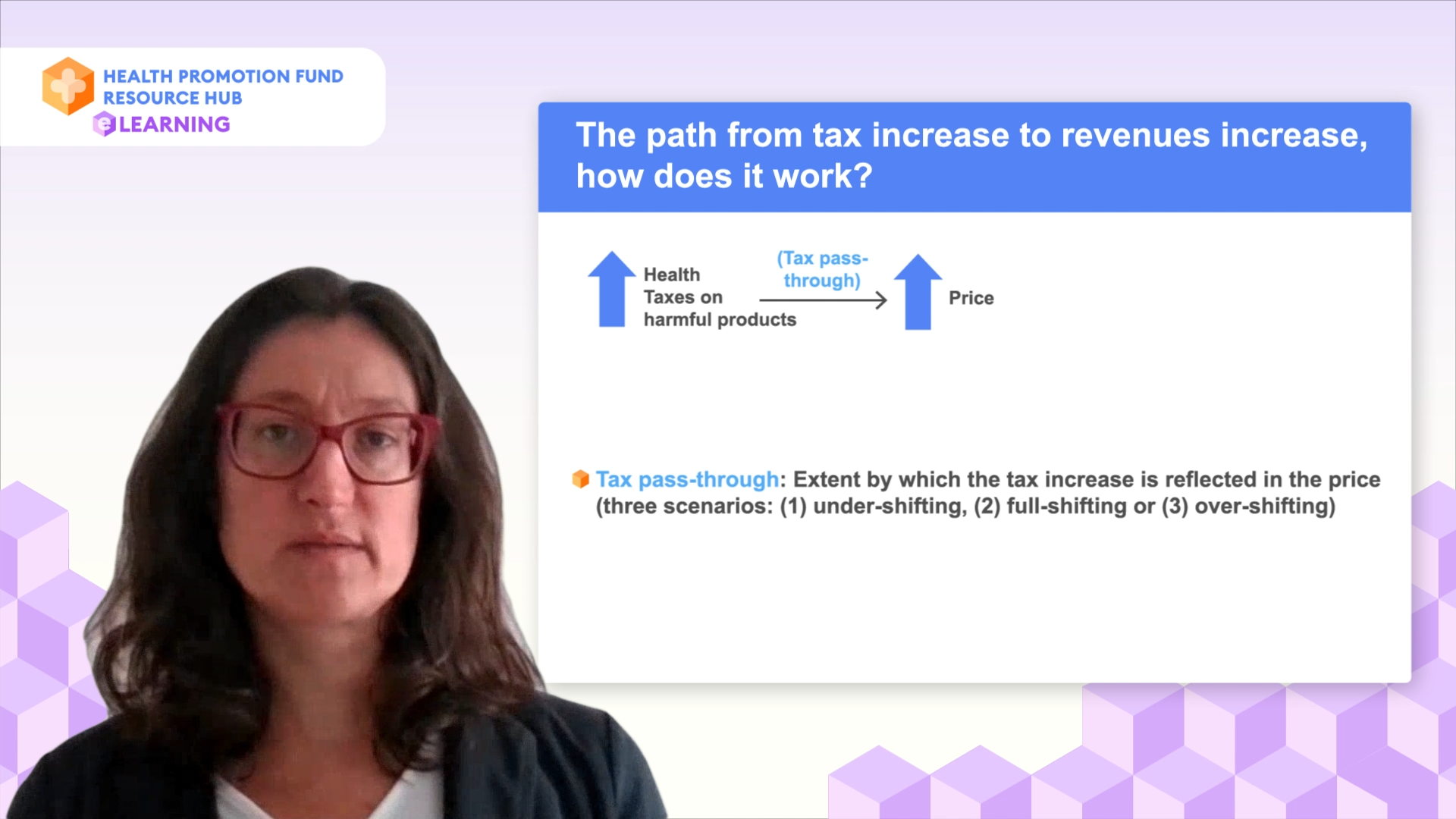

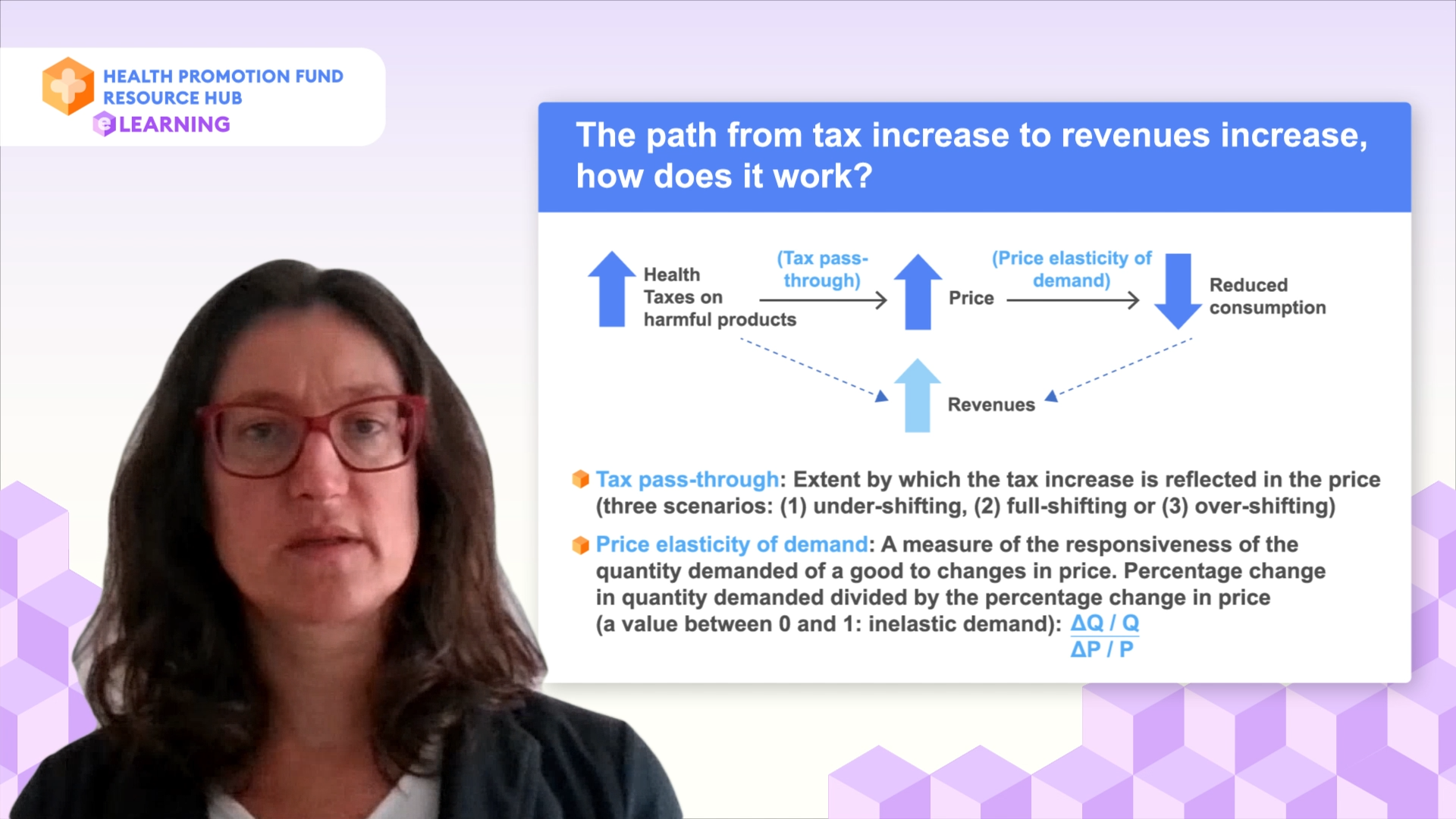

Following the previous slide, let’s go in more detail into the path from the tax increase to the revenue increase. As the tax on harmful products increases, given different market dynamics but also if the tax increase is large enough, the tax is passed on to the price leading to a large enough price increase.

This is what we call tax pass-through which is the extent by which the tax increase is reflected in the price. There are usually three scenarios, the first one (1) what we call under-shifting, when the industry absorb part of the tax and the price is not increasing by as much, (2) full-shifting, when the price increases as much as tax increases, and (3) over-shifting, when the price increases more than the tax increase.

As price increases, consumers who are sensitive to what affects their wallet will reduce their consumption by a certain quantity, this is what we call the price elasticity of demand. The price elasticity of demand is a measure of the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good to changes in price. It is the percentage change in quantity demanded (Q) divided by the percentage change in price (P) as you can see in the equation on the slide.

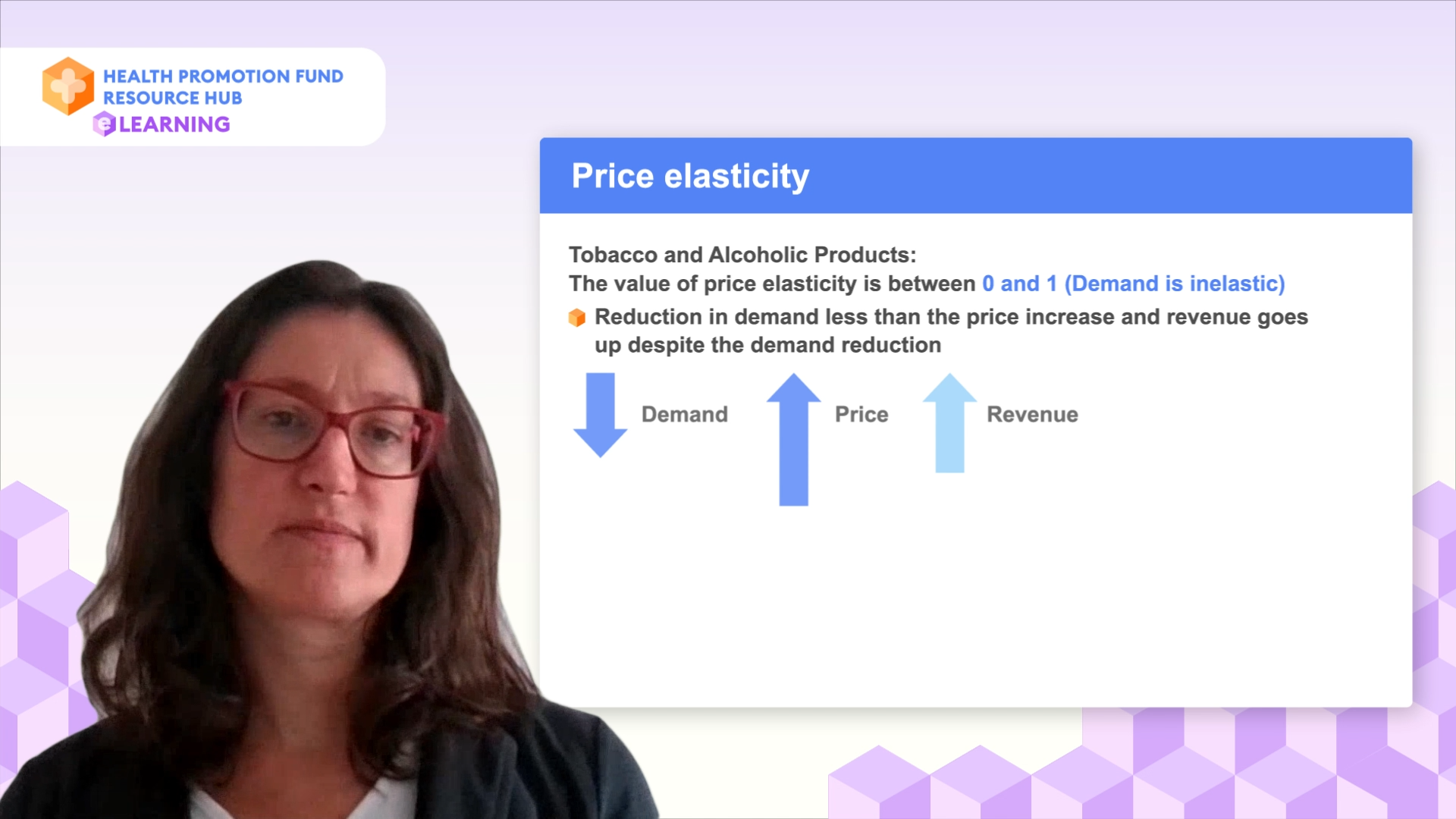

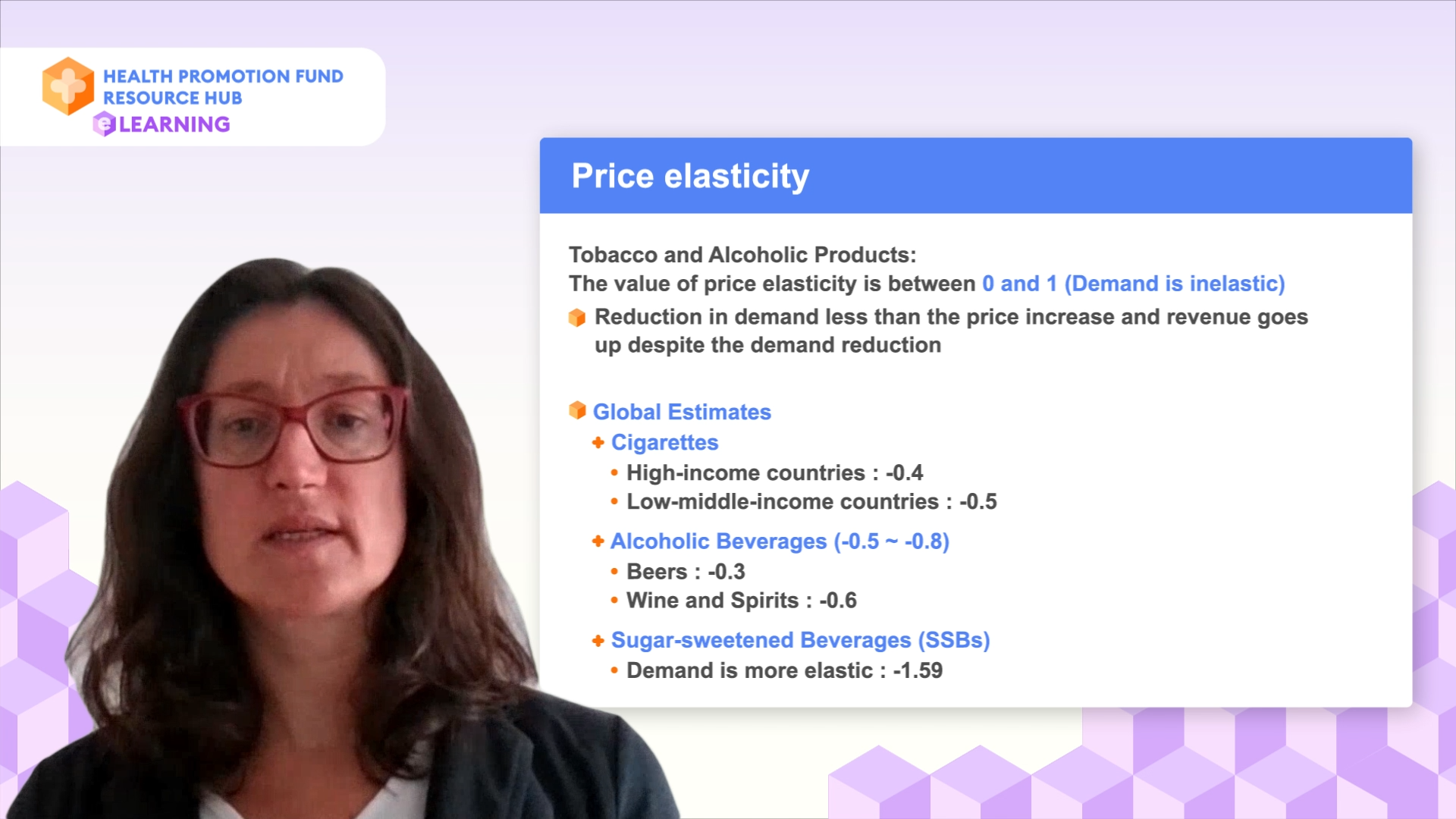

In the case of tobacco and alcoholic products, the value of price elasticity is between 0 and 1, in negative terms, which means that demand is inelastic. This means that the reduction in demand will proportionately go down less than the increase in price. This is one component which makes revenues go up despite a reduction in demand.

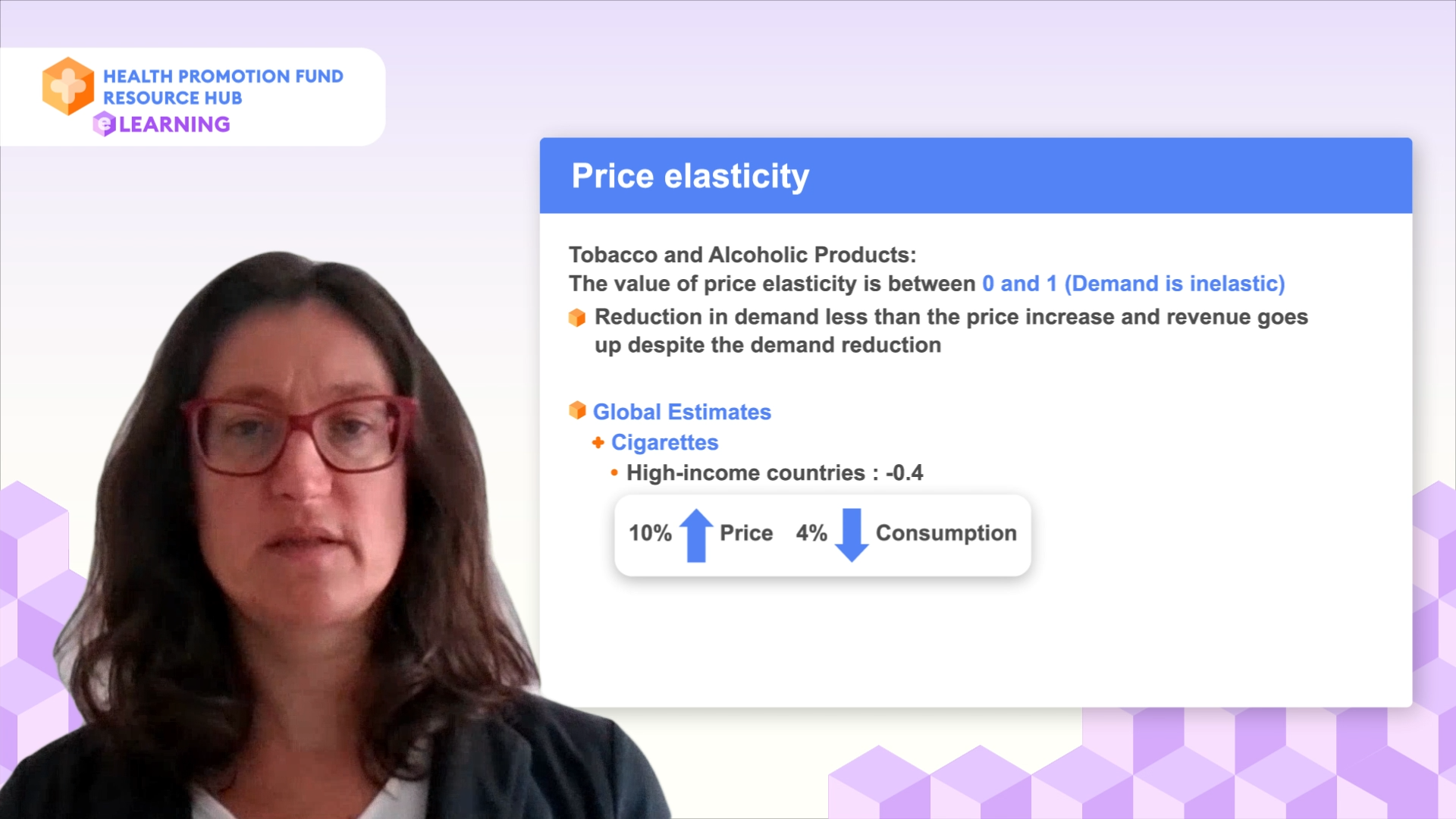

Global estimates show that price elasticity amounts to: For cigarettes, in high-income countries, price elasticity is -0.4, this means that an increase of prices of 10% reduces consumption by 4%.

In low-and middle-income countries, elasticity is higher at around -0.5. For alcoholic beverages, elasticity ranges overall between -0.5 and -0.8. In relation to specific products: -0.3 for beers, and demand is more elastic for wine and spirits with an elasticity around -0.6. For SSBs, demand is more elastic and it is estimated to be at around -1.59.

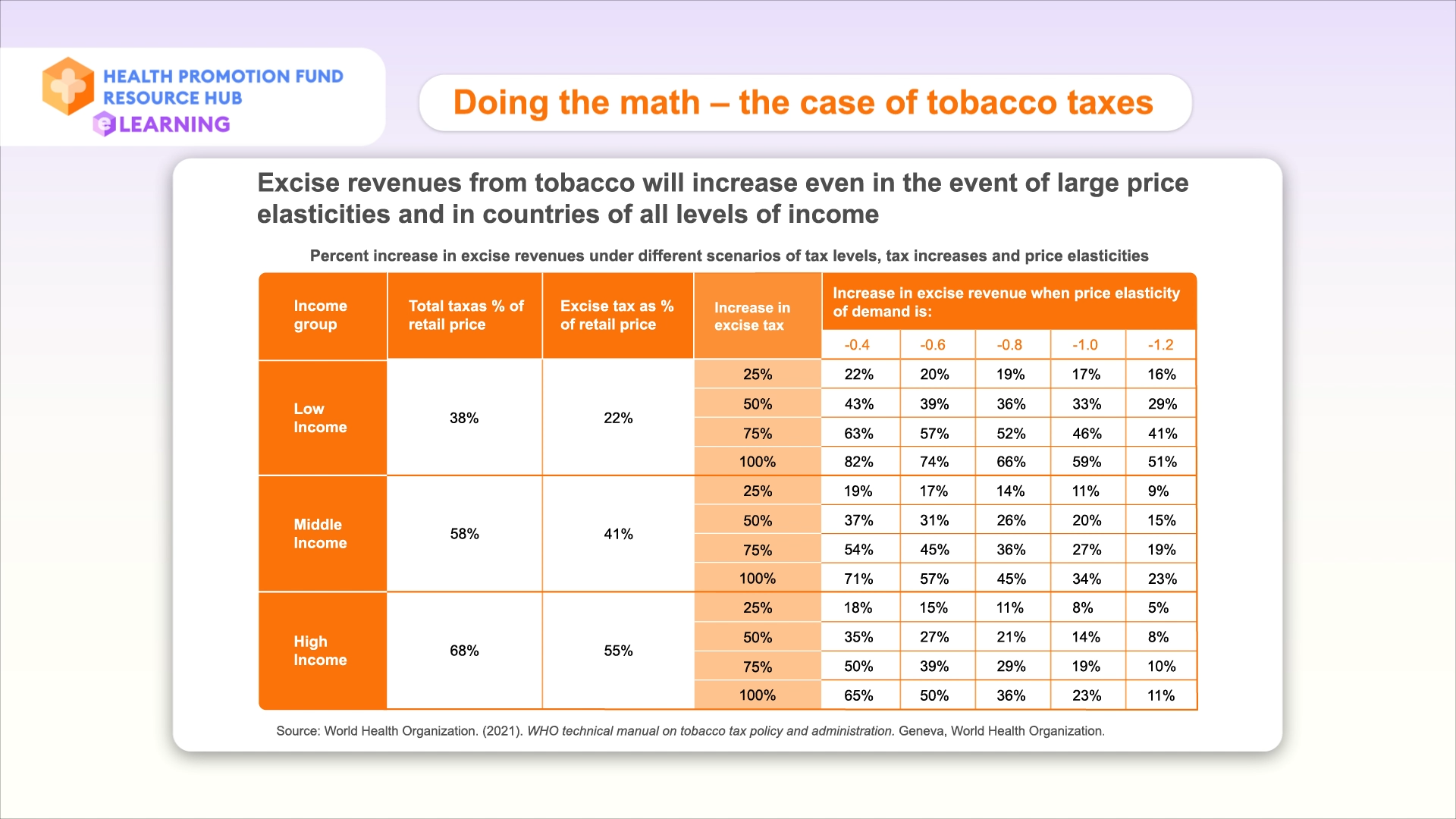

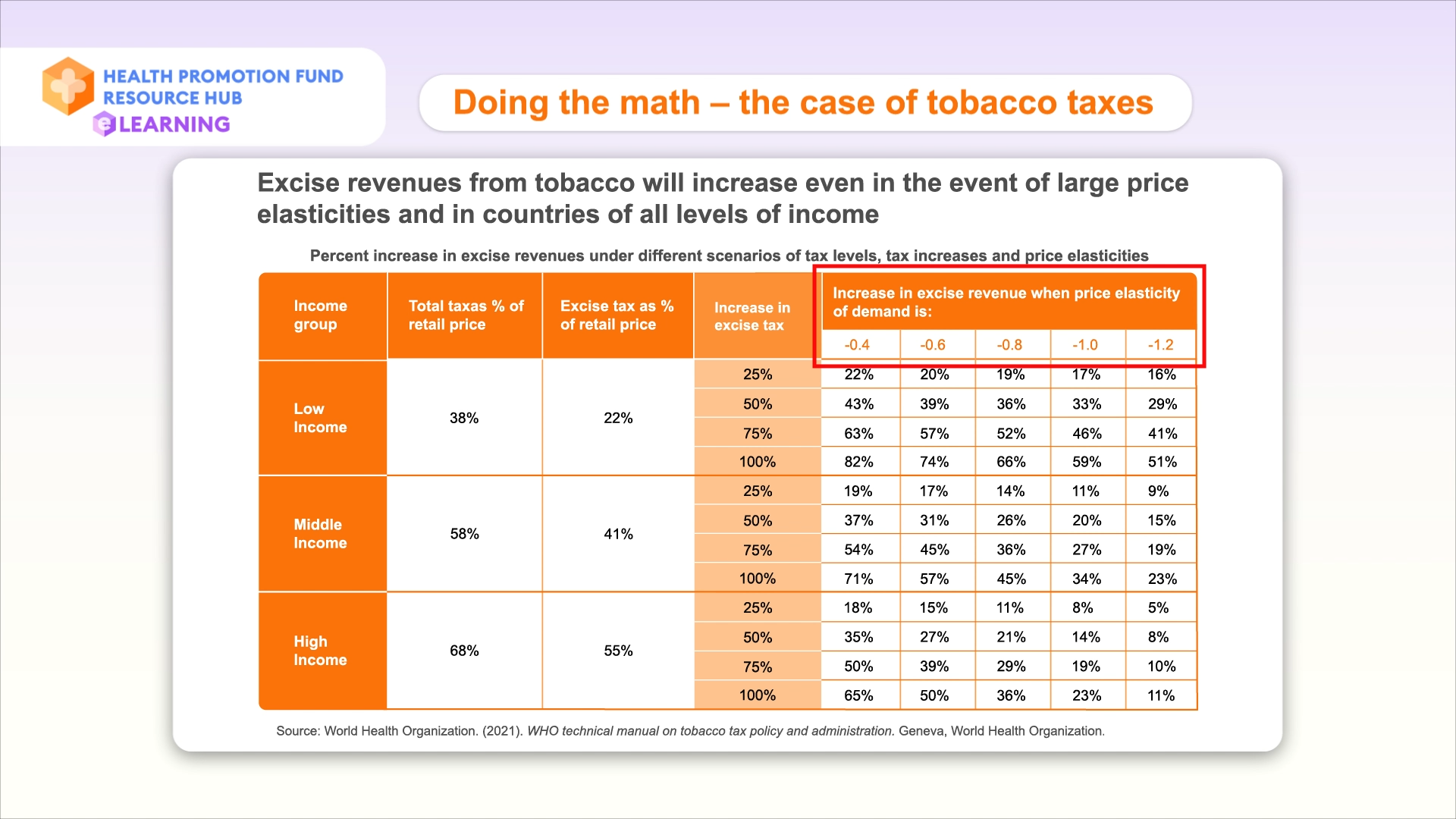

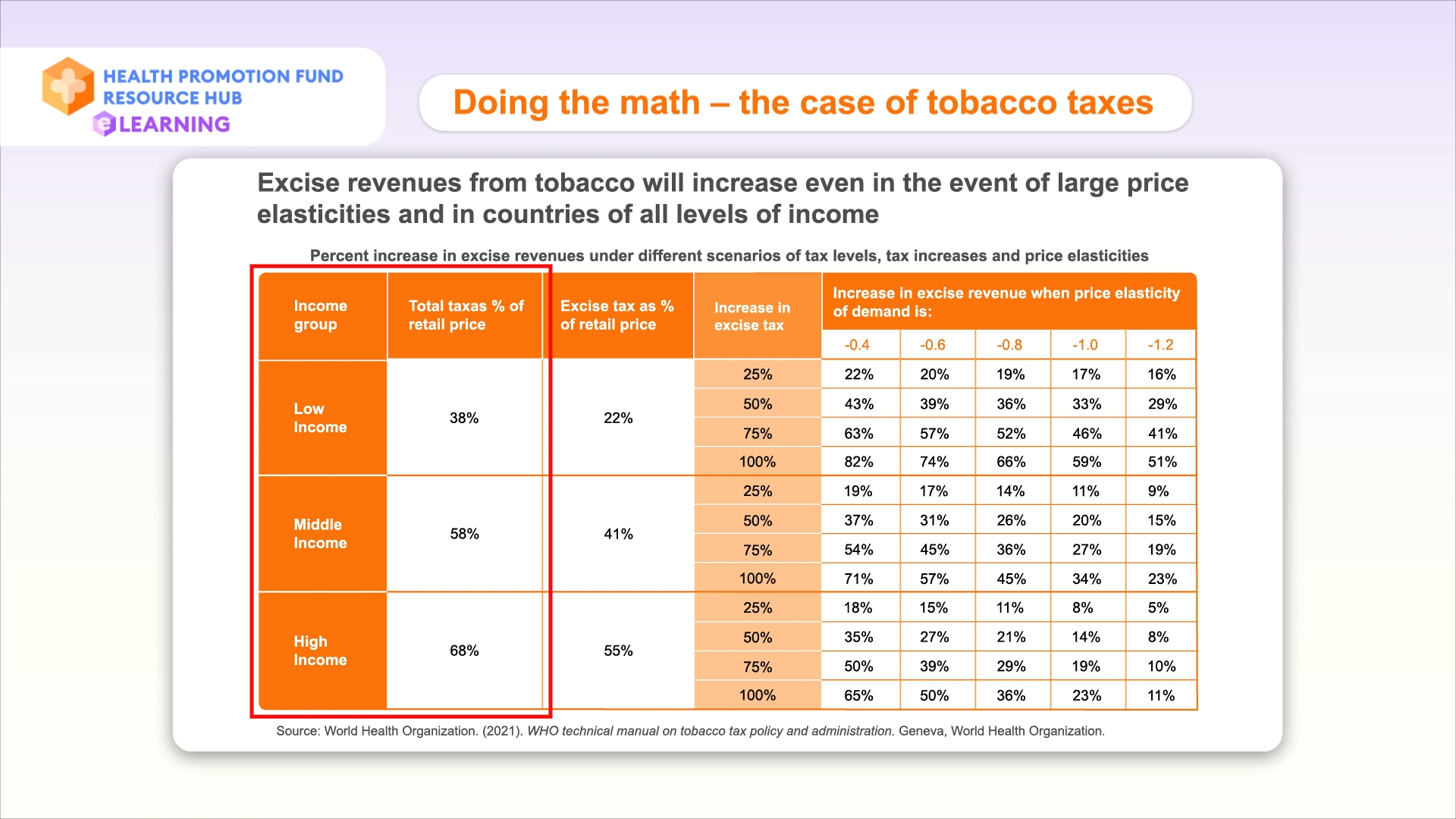

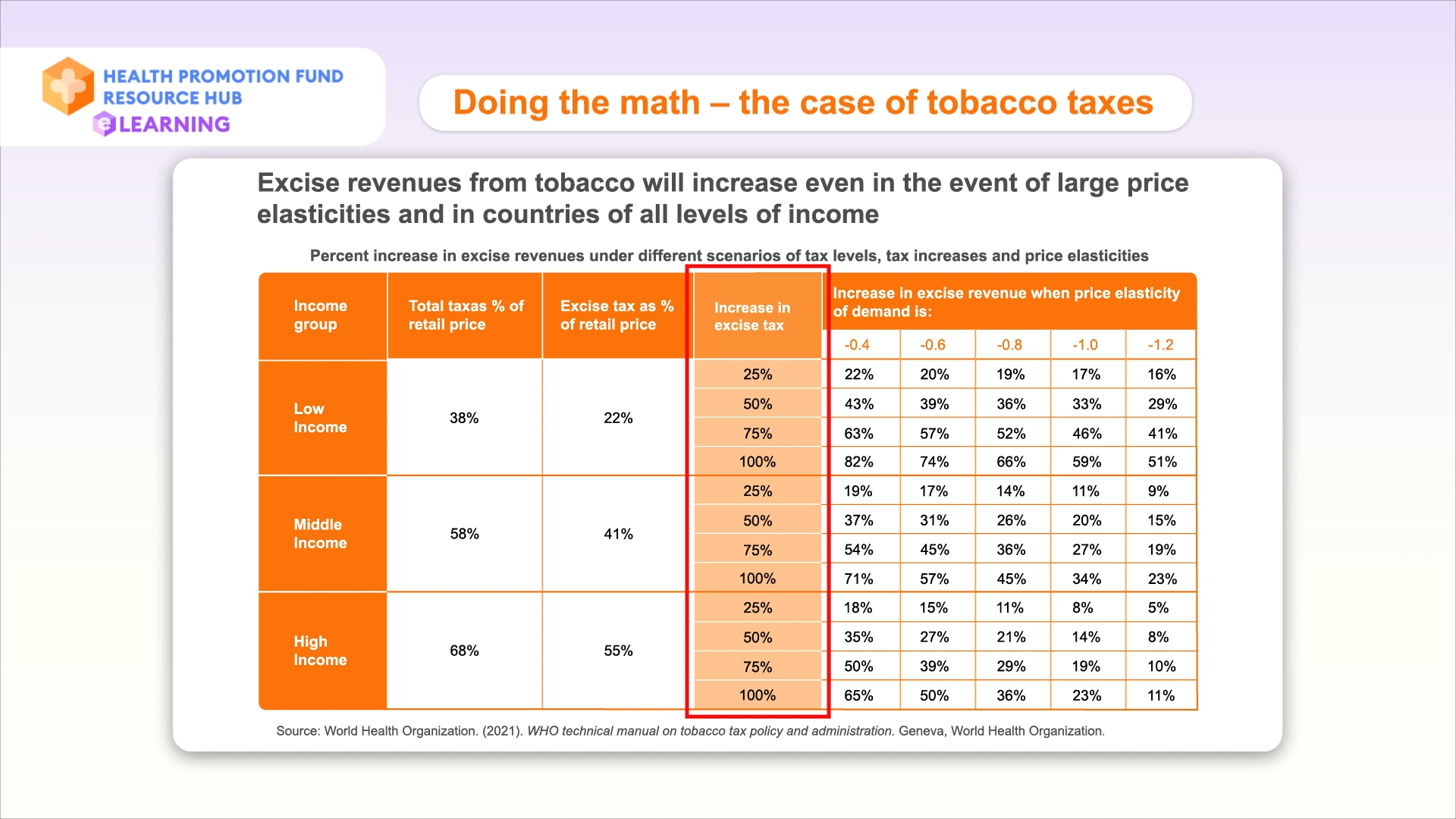

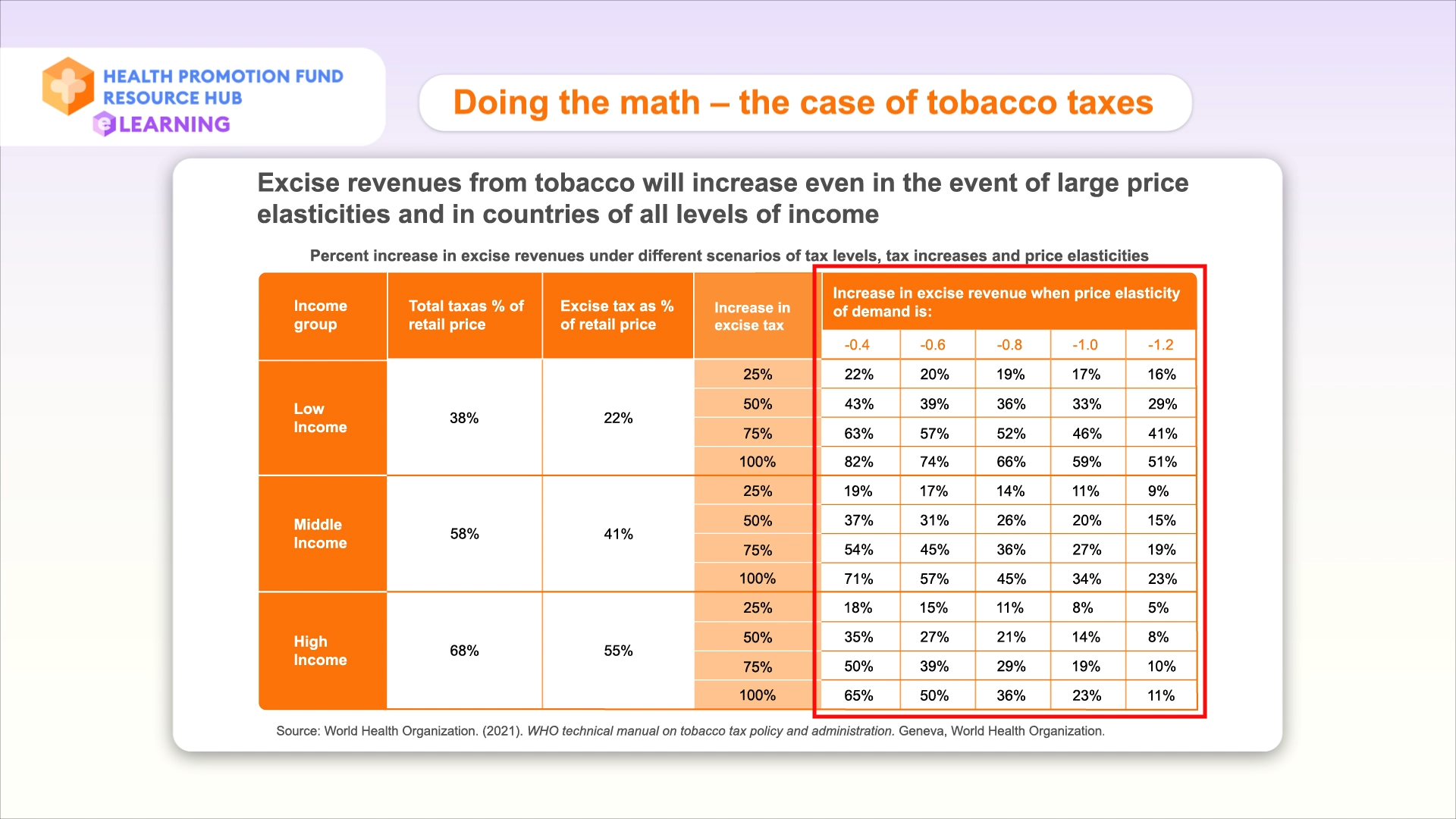

If we do the math, let’s look at current implementation of tobacco taxes globally and across country income groups.

Let’s consider different scenarios of price elasticity from least elastic (elasticity of -0.4) to most elastic (-1.2) and with income groups with lower tax share around 38% as estimated of the retail price of cigarettes to higher level around 68%.

In all scenarios considered in this table, we will look at the impact of tax increases raising from 25% to 100% all will generate increases in revenues.

So the argument that increased taxes would generate fewer revenues does not hold even with high price elasticity and with high taxes and there remains space in all settings to increase taxes and get more revenues.

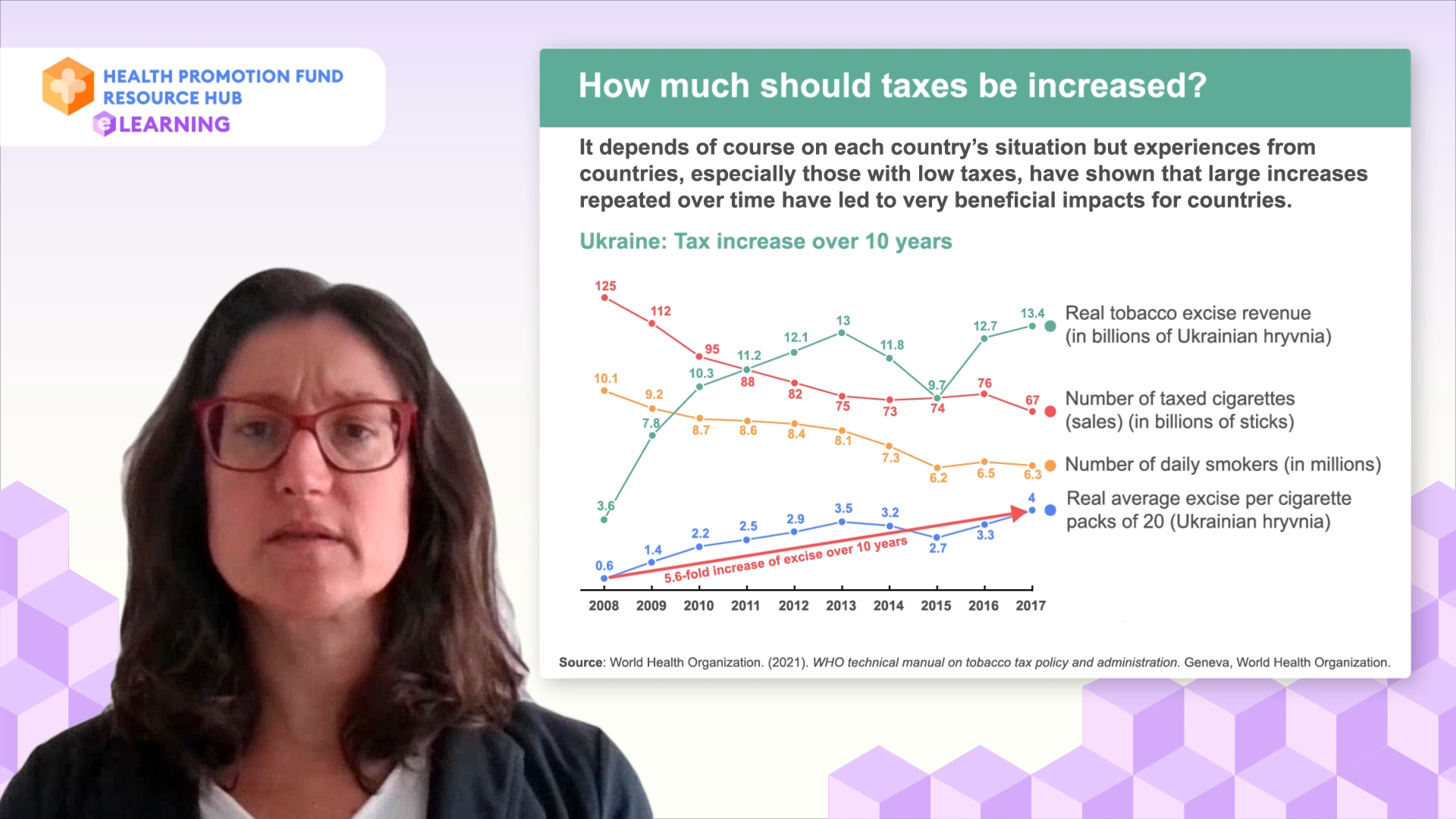

So how much should taxes be increased? It depends of course on each country’s situation but experiences from many countries, especially those with low taxes, have shown that large increases repeated over time have led to very beneficial impacts for countries. We have here examples of Ukraine and Columbia. In Ukraine, we can see in the graph that over a period of 10 years, an increase in taxes of 5-fold has led to revenues to more than double while sales halved and the number of smokers decreased by almost 40%.

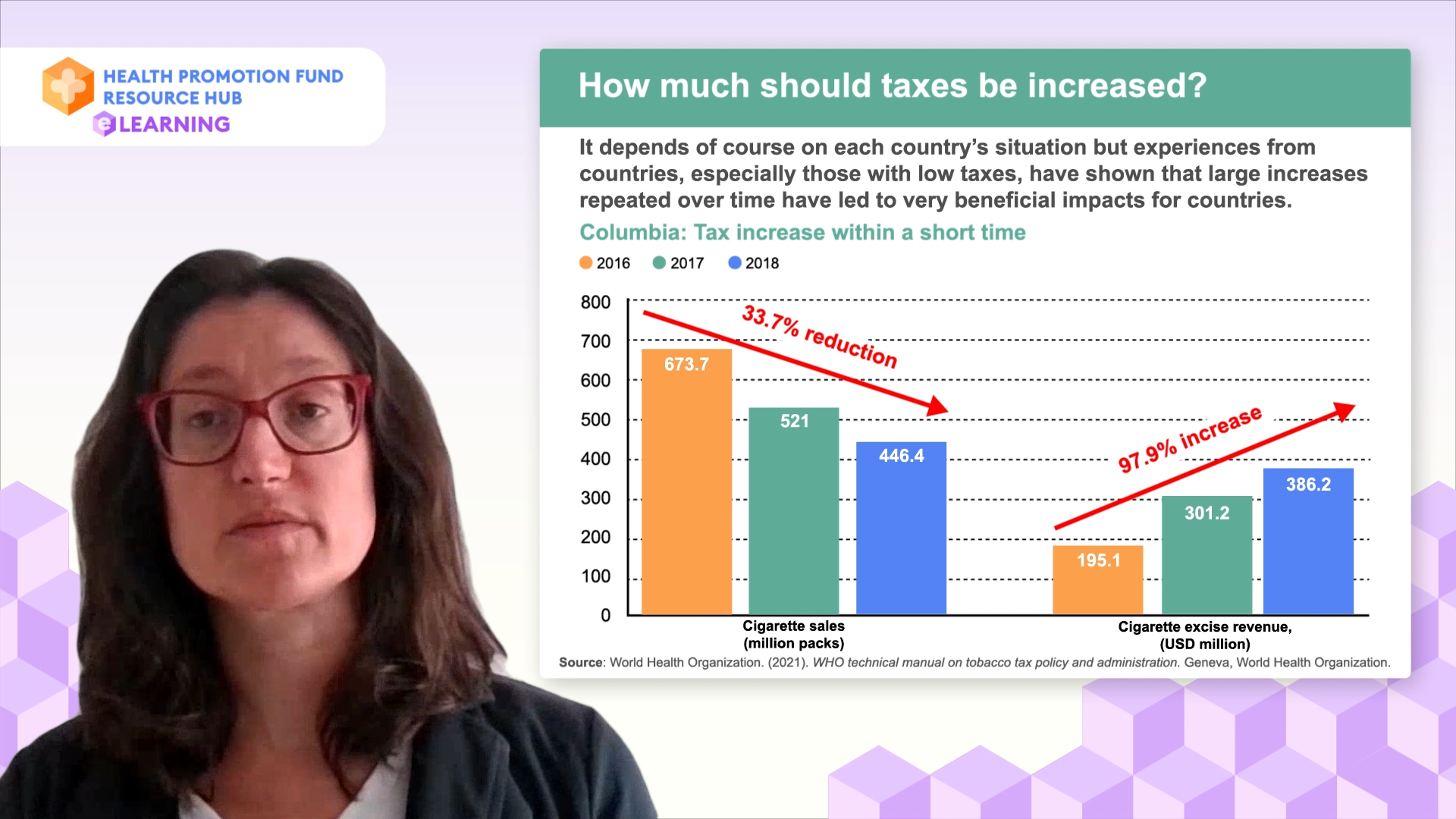

In the case of Colombia, taxes more than doubled within a very short time-frame period and this has led to revenues to double while sales went down by more than a third.

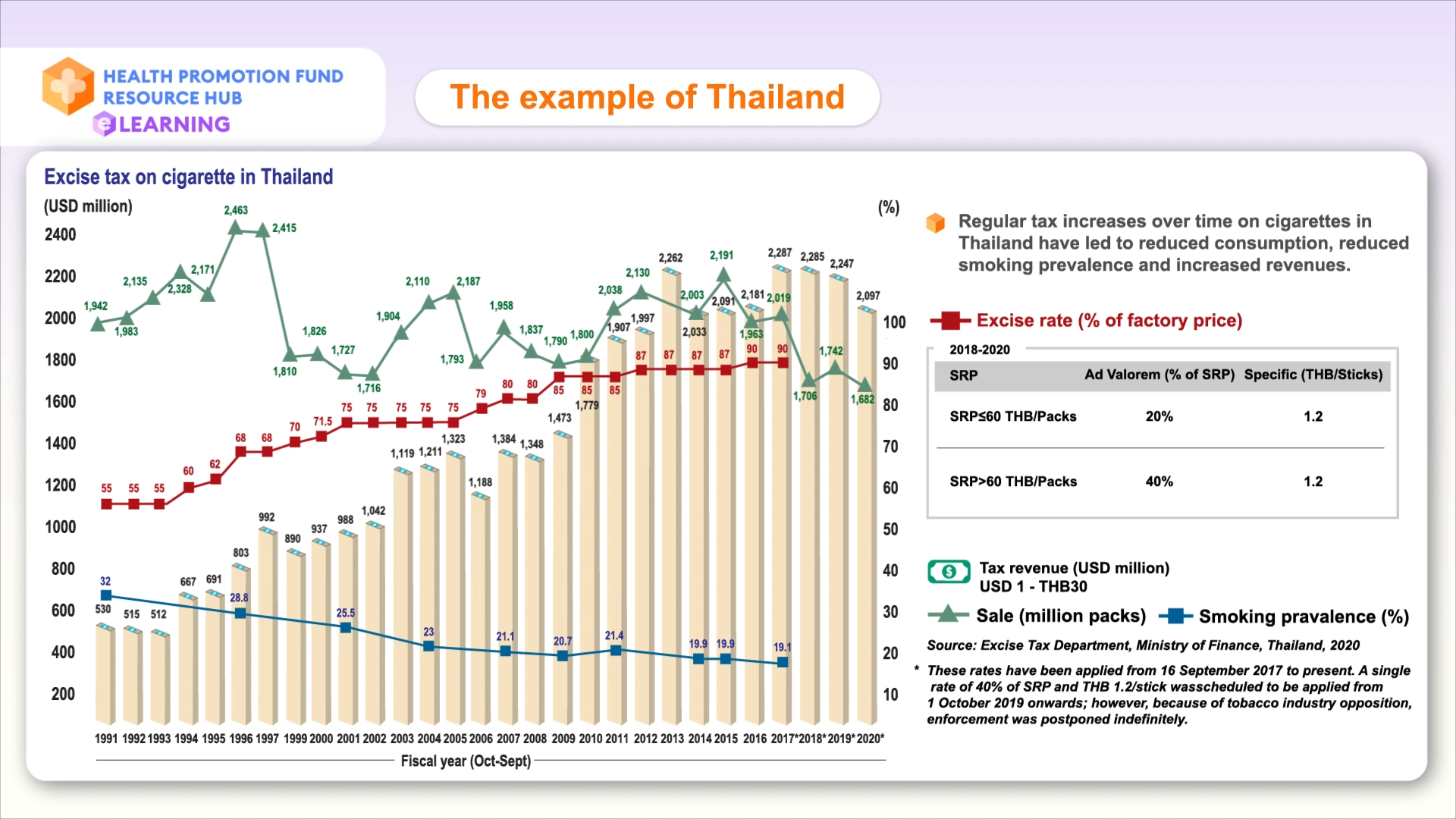

Finally, let’s look into the example of Thailand, where regular tax increases over time on cigarettes in the country have led to reduced consumption, reduced smoking prevalence, and increased revenues. In the graph, we can see tax rate increased regularly over a period of 30 years (almost doubled), and this is followed by reductions in sales and prevalence from 32% to 19.1% and revenues increasing almost threefold.

So it is clear, tax increases leading to increases in prices which makes products less affordable will reduce consumption while at the same time increasing revenues for governments..

For this module, we have learned about the health and economic burden of consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages and how health taxation is good for health and the economy. We have also explained the path between the tax increase and the impact on health and the economy. We have also gone over the experience of a few countries that have regularly increased taxes and have experienced reductions in consumption and increases in revenues. If there is one message to take from this module, it is that health taxes have a great potential to improve populations’ health while at the same time, generating much-needed additional revenues for countries but their potential is still untapped and they should be scaled up.